|

| 5th Street Apiary mead |

You see, after thinking long and hard about the sustainability of the apiary and the welfare of the bees, Grant and I have made a strategic business decision. We got married. Yes, it is a sacrifice, but one that we are willing to make for the ladies. We committed ourselves to each other in early October.

This is why we’ve been scarcely able to blog about any of the fun stuff happening in the beeyard, though we do apologize about the long hiatus. We’ve been making mead for the wedding, donning another kind of veil, and yes, we just returned from our honeymoon.

An announcement about our honey

In the midst of all the flurry, we have also been selling some honey! So much so, that we have another announcement to make. We are sold out of honey for 2011.

We've been really excited about the great reviews our honey has received and we'd like to thank everyone who has supported us so far. We look forward to growing so we can get more honey to more friends!

|

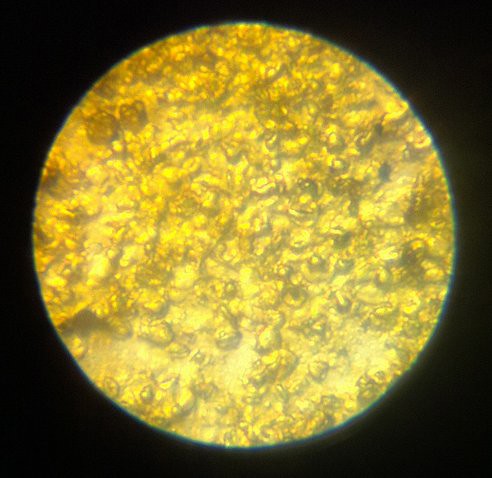

| beeswax lip balm |

An announcement about a new product

We introduced our lip balm this summer at the markets where we sold, but barely breathed a word of it on the internets. But we sell lip balm now, too! We collect beeswax from the ladies and add sweet almond oil, shea butter, cocoa butter, and various essential oils to make these little lovelies. We sell them for $3 each and currently offer three flavors:

peppermint eucalyptus

rose geranium

mojito (lime, peppermint & honey).

If you are interested in any of these to prep for the encroaching winter, let us know at 5thstapiary@gmail.com.

We introduced our lip balm this summer at the markets where we sold, but barely breathed a word of it on the internets. But we sell lip balm now, too! We collect beeswax from the ladies and add sweet almond oil, shea butter, cocoa butter, and various essential oils to make these little lovelies. We sell them for $3 each and currently offer three flavors:

peppermint eucalyptus

rose geranium

mojito (lime, peppermint & honey).

If you are interested in any of these to prep for the encroaching winter, let us know at 5thstapiary@gmail.com.